Beliefs

In our formative years the brain has only one function and that is to initiate behaviours that allow us to survive. Of course, this fundamental truth can get lost as our interactions with our outside environment get more complex but all behaviour can be traced back to that central truth. Just how powerful this drive is can be demonstrated every day in emergency wards where people’s brains have shut down every activity but the bare minimum – they are comatose. This simple fact that would make understanding behaviour reasonably simple but life’s not simple and the rising, tragic levels of suicide provides the exception to the foundational rule; survival is the prime drive for behaviour! I will argue that individuals select not to survive because of their learned beliefs and these beliefs are more powerful than evidence the evidence from their immediate environment. (This Newsletter follows that of the 11th June 2019 – Faulty Beliefs).

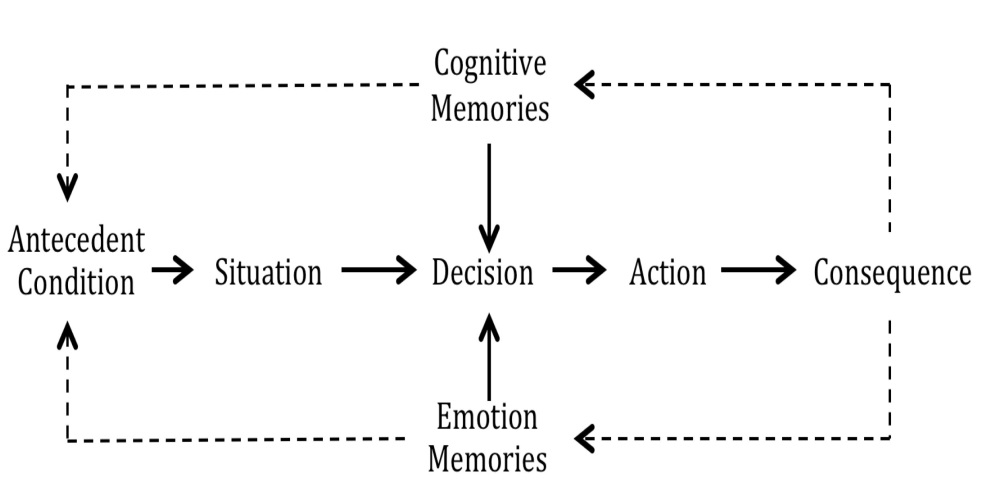

Despite the anomaly of suicide, the brain’s purpose is to facilitate behaviours that allow us to survive. The model below helps us understand this process:

At the heart of this model is the link between situation, the presenting environment, our actions and the consequences. That is, we find ourselves in a threatening situation and we act to alleviate the stress caused by that situation. The resulting outcome is noted and ‘stored’ for future reference, that is it is remembered. This is the feedback loop in the model above. Successful responses will be reinforced and be available whenever a similar situation occurs.

In early childhood these memories are emotional, that is when we find ourselves in a situation similar to a previous threatening one, our emotional memory of that early encounter will evoke a response. That ‘feeling’ is the first expression of a belief! Later, when our brain matures we develop cognitive memories that function the same way but put reason to the stress we experience and this motivates us to act. This is the lower feedback loop in the model. We build up a sophisticated internal map of our ‘world’ and how the conditions it presents impacts onto our homeostatic state. These memories inform our decisions on how to act!

Initially, the sequence follows the observation of the threat, that is our senses alert us to the danger, they provide the data that drives the behaviour. But, one of the things that has allowed us to become the most successful species is our ability to use the memories we have built up to imagine or anticipate impending problems. These are as fundamental as having been threatened by a crocodile in a stream one day we become extremely cautious when we approach the stream on subsequent days. That is, we have a belief that there will probably be a crocodile if we go near that stream another day and so when we approach we will be anxious and consequently more cautious even though there is no sensory evidence, no data that indicates the presence of a threatening reptile.

The internal map of memories, beliefs allow us to ‘know’ things that are not relative to the data in our immediate circumstance. The authority of our belief systems is such that we can navigate our way around the world. If we were limited to act just on the explicit evidence we would be stuck in space. As I write this I have a belief that my car is in the driveway yet I have absolutely no direct data to confirm this, I just ‘know it’, beliefs are powerful tools. In fact, I could not even find my driveway except through clumsy and time-consuming trial and error if I didn’t ‘know’ where to turn as I go through the house!

So, we have two systems that regulate our behaviour. The first is incoming data – things like a car speeding towards us in a threatening manner, we will ‘decide’ to jump out of the way. The second is to always look both ways before we go onto the street because we believe it is possible that a car might threaten our safety even though we can’t know if a car is there without checking the data. The belief produces behaviours that ensure our safety even though there is no immediate evidence. We become careful!

The two systems that are equally important, serve the same purpose but are different. Our senses provide the data to perceive our immediate world. Our beliefs, our memories let us understand our world outside the confines of our perceptions and provides reasons for choosing protective behaviours. These operate independently and the brain only cares about how helpful either system is for its survival.

In the model, the feedback from the memories to the ‘antecedent conditions’ reveals the impact our ‘beliefs’ have on the way we view our environment. That is when we are confronted with any situation our perception of the incoming stimulus is influenced by previous experience. For most, this has given us a huge advantage in successfully managing our lives but, there is a malicious disadvantage for those whose memories are of abuse or neglect.

The students at the heart of these Newsletters invariably suffer from Toxic Shame (see Newsletter – 3rd July 2017) which results in a set of beliefs that are relevant to the abusive/neglectful environment in which they were developed. It takes some effort to understand how such a destructive set of beliefs could emerge in a child but if we put ourselves in their position we would see that these beliefs gave them the best chance of survival. Even the idea that they are worthless can reflect any circumstance where they felt worthwhile. Feeling valued could initiate a sense that you should ‘fight back’, defend yourself but for a child with an abusive parent any such sign of assertiveness would be crushed. It is safer to believe that defective image.

At school these children experience a positive environment where the senses, the data is or should be non-threatening and supportive. If you take the example of the crocodile in the river, the calm supportive environment may well be present but these kids know the possibility ‘of a croc lying in wait if the drop their guard’. The presence of a reassuring setting should make the child suppose things are safe and they can act in an appropriate way to get their needs met. But, of course they don’t! These kids remain suspicious, there may well be a croc lurking below the surface. Teachers get frustrated when they provide all the support for these children but their behaviour doesn’t easily change!

The answer is in the fact that these beliefs developed over a period of time and they drove the behaviour that was the most likely to ensure security. That is the situation, the pattern of environmental factors was not the exclusive one but the most likely. The brain learned to dismiss those that did not fit that arrangement.

When the child who has developed a strong belief about their sense of self has that challenged, is presented with an alternate supportive set of data, this dissimilar event on its own will not over-ride the beliefs. This may be a ‘one-off’ occurrence and we can still remember what could be coming next! Deep held beliefs are hard to change even in the face of over whelming evidence.

Take the argument about evolution and the conflict it has with those who believe in intelligent design, the Bible. These people cling to a very strong commitment to that story and any counter claim, evolution is denied despite all the evidence put to them. To accept they were wrong is a perceived, direct threat to their survival. Even a small concession would unravel the whole system and so they will defend even the most bizarre claims with what others would find preposterous. It is tempting to dismiss these people but if you understand they really have this belief system you realize they are not stupid.

The same goes for our kids. Too often I see well-meaning teachers take these kids on an excursion, say to an adventure style park where they successfully experience abseiling, rock climbing, etc. This, one-off adventure will not change their beliefs, it is just that a ‘one off set of data’ is no match for their beliefs. One problem is these adventure programs are run by non-school staff and they see the excitement of each group of students as they go through their courses and they think they are successful. But the kids return to school and not much has changed for these kids. Unfortunately, the teachers ‘see’ the kids cope with the challenges they face on these courses but get discourage when the kids, despite this evidence don’t change!

Beliefs can be changed but be prepared for a long process that must include an environment that consistently provides the ‘proper, positive data’ and a messenger that is acceptable. There is no surprise in the appreciation of the importance of the relationship between the student and the teacher. This is at the heart of all learning!

Although the data may ‘shout’ at the student, if it threatens them they will shout back. There is absolutely no value in confronting these students when they are under threat. The teacher must patiently wait for the right time and quietly offer an alternate view of the situation and their safety. Remember, the feeling of being under threat will be expressed in the emotional memories. If the child feels threatened enough their protective behaviours will emerge and they will go into a state of flight or fight. The teacher must remain calm and remain present!

To change beliefs takes a skilled teacher with a well set-up classroom and one who is prepared to chip away at the student’s faulty beliefs. They have to be the right person with the right data at the right time! And they need to be very patient. It is hard to turn these kids around but it will be the most rewarding teaching you will ever do!